A longer and more comprehensive version published in RSD12 as a Proceeding Paper.

In the field of design related to multi-actor experiences like service design or whatever else is emerging, we often see specific barriers or challenges that one or multiple actors encounter that impede them from reaching their goals or make their experiences less than optimal—we usually call them “pain points.” The standard practice, for example, is identifying and categorizing pain points in a qualitative research analysis.

While we can intuitively identify what a pain point looks like, as designers, we have the proclivity to inquire deeper as to the causes of those pain points: to expose the ‘why’s’ of those pain points (I will refer to “pain points” and “pains” interchangeably from here on). Usually, we would find a misalignment between expectation and reality that culminates into pain. Thus, we can think of pain points as consequences of those fundamental contradictions. As experiences and observations have taught us, not all pain points are the same. For example, a situation where a service recipient says, “I want to find the exit, but it’s so confusing to navigate.” Suppose the service deliverer, say an organization, agrees, “we want the user to be able to navigate out quickly to make room for others,” then the fix is quite straightforward. What if in another situation, where similarly “I want to find the exit, but it’s so confusing to navigate,” only this time the organization feels “great, but we want the user to stay longer as it benefits us”(think of the mall or retail space)? We can see how the pain in the first situation needs to be approached differently than in the second situation.

Pain Points and Intention

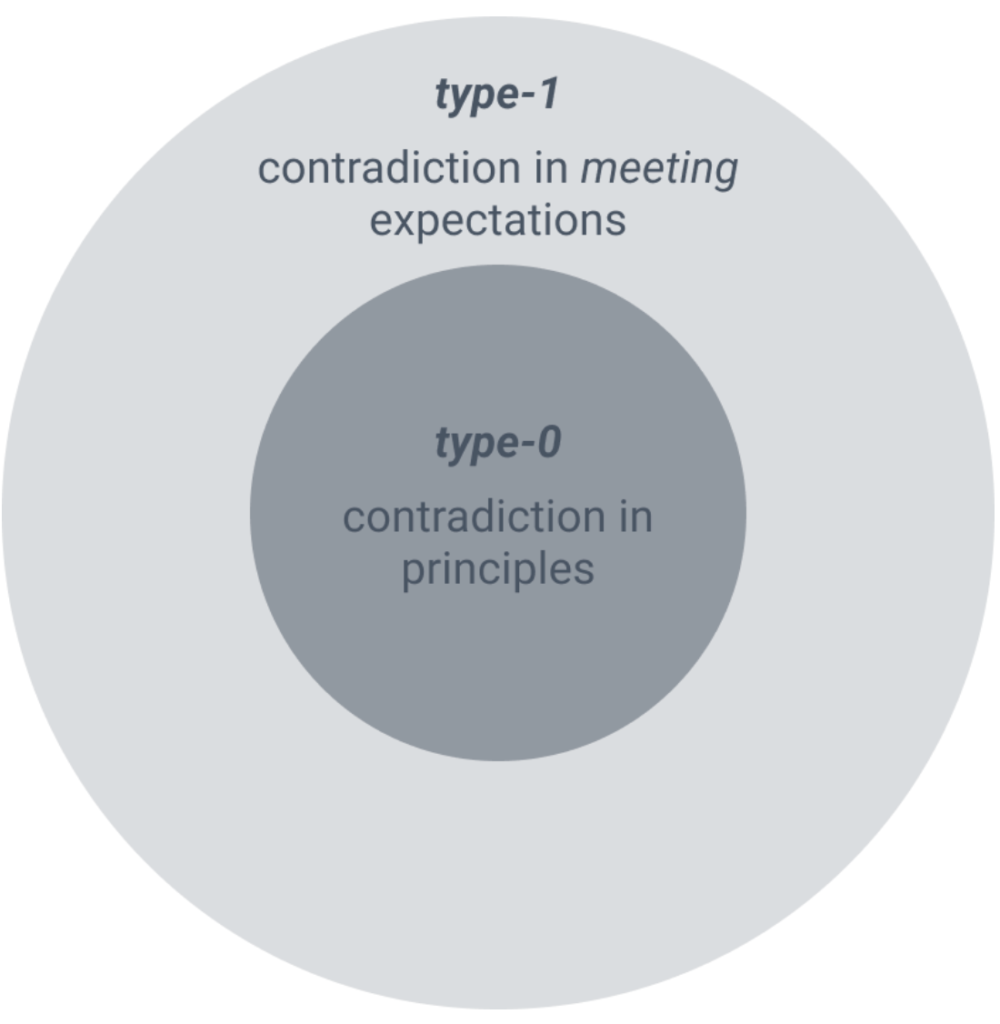

What we can derive from the examples above is that, in a simplified form, there are generally two kinds of pain points—we can roughly define them:

- Contradiction in meeting expectations means the pain occurs when things do not apparently or actually work as intended by both the service recipient and the service delivery. There are two scenarios here that fall under this category — (i) where the service deliverers believe they provide what the recipients want, but it wasn’t, that they’re not designing the right thing, and (ii) where the service deliverers believe they provide what the recipients want correctly, but it was faulty; that the thing is not designed right.

- Contradiction in principles means the pain occurs because it is purposefully designed in such a way according to some inherent and underlying principles. Bear in mind that this could mean different things, and they don’t necessarily mean the intent is in any way always unethical —though some of them are definitely done so. For example, what we formally call a “dark pattern” in UI design would fall under the contradiction in principles, where things are intentionally designed for those consequences. But, design outcomes based on the constraints of rules and regulations, or corporations’ goals to make profits, also fall under this category.

In all instances, the entry point of a qualitative investigation would generally begin with the pain of the actor. Where the pain category gets escalated is when we discover that the way things are designed is under the directives of certain organizational goals. These goals do not always align with service recipients’ goals. A classic example in the field of design is planned obsolescence, where consumers want their products to last for as long as possible, but the corporations that make those products would benefit more if the product’s shelf life is short. That is a contradiction in principle. Thus, we can outline the two types of pain into a kind of hierarchy; for a contradiction in expectations, we can call it a type-1, and for a contradiction in principles, we can call it a type-0—something like this1:

The abstracted examples above demonstrate the delineation of different types of pain. We understand that the reality of the situation is always much more complicated. But where the categories above would be useful for design practitioners and theorists alike is to be able to design appropriate solutions on an appropriate scope. Namely, we can only sometimes use local solutions if the problem is global. In other words, systemic problems need systemic change, but only if we’re able or understand the need to identify what the systemic problems are.

Thus, based on the types of pain proposed above, it would be useful for us to think about ecosystems and structures. Namely, each actor’s behaviors are governed, in some ways or others, by a certain structure that, in turn, influences culture, habit, and so on, that surrounds it. Suppose we accept that different people have different ecosystems surrounding them when interacting. In that case, the focus should not be just on the ecosystem of the service providers but on the service recipient side. Often, we investigate user behaviors as a persona or an instance of individuals in themselves. Still, they bring their world with them and are in constant interface with other worlds.

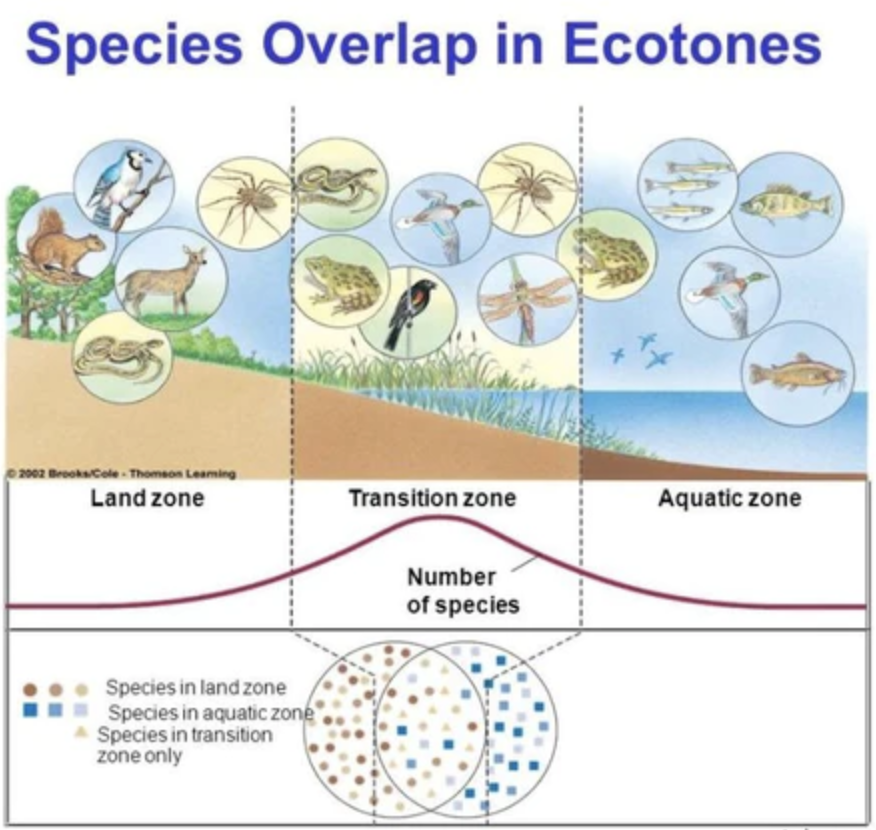

Ecotone: A transition of Ecosystems

We can borrow a concept from ecology called the ‘ecotone.’ An ecotone can be understood as an area “of transition between ecological communities, ecosystems, or ecological regions.” The concept of an ecotone assumes “the existence of active interaction between two or more ecosystems with properties that do not exist in either of the adjacent ecosystems” (Leemans, 2013, p. 148). Some ecological examples include grassland as an ecotone between a forest and a desert, an estuary between fresh and saltwater, and a marshland between dry and wet ecosystems.

The concept of ecotones is also being applied in domains outside of ecology. For example, an architecture professor, Ann Pendleton-Jullian, used the concept of ecotone for “architectural design education” that “proposes a sustainable educational environment: a spec of pervasive innovation that is talent-rich and talent diverse.” (p. 113–114). Similarly, an ecotone is used in postdigital education, for example, by Ryberg et al., beyond the conceptual to include the space and material dimensions—as “innovation ecotones.” One example provided is the Architecture and Design programme students’ workspace which they call “Digital and Material Infrastructures.” They noted that:

“The layout of the space develops over time, as activities change… From an immediate glance, the picture seems to convey primarily physical and material practices, but one can find traces of the digital as well. Several of the papers hanging on the pinboards are prints of computer designs, pictures, or sketches… Many of these pictures were printed from Pinterest. Either the groups’ own pins from Pinterest or those from the digital pinboards shared across the entire semester… all groups had to maintain an open Google+ group presence and share designs and Pinterest boards with the other groups. In this way, an online presence or online studio was available for each group so the groups could communicate and explore each other’s designs both onsite and online. The physical and online spaces were closely connected.” (Ryberg et al., 2021)

Ecotones in Service Design

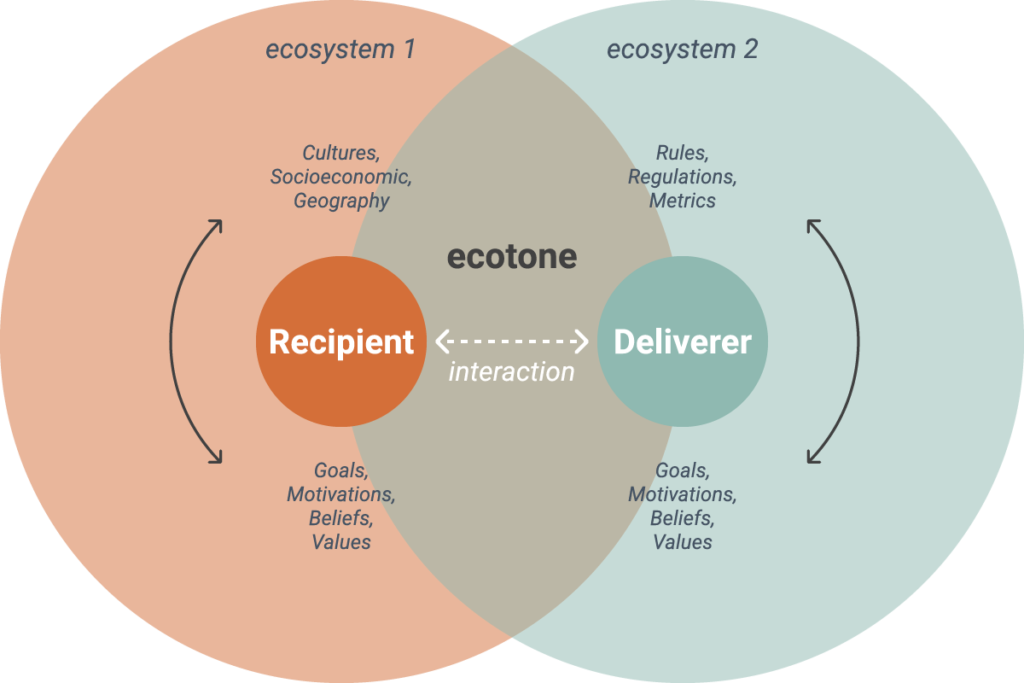

In service design, however, we could think of an ecotone as the overlapped and tensioned2 area/zone between the service deliverer and service recipient because each brings with them not only their mental models; beliefs, knowledge, understanding, but also the rules and structure that shapes their behaviors and state of minds, i.e., their ecosystems. Even different touchpoints in a single service can have ecotones.

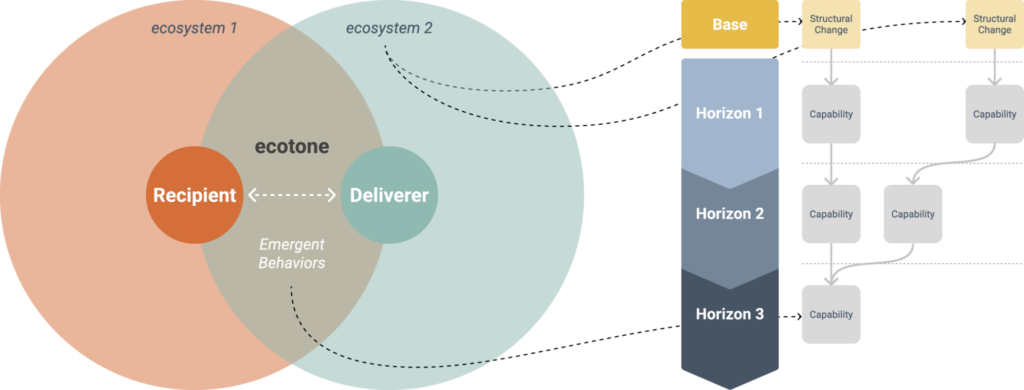

We can also think about the clashing models and interaction patterns between different partners in service delivery. Even different touchpoints in a single service can have ecotones. This framework aims to push our qualitative research and surface some hints about the “why’s” of the actors’ behaviors from a systems perspective. Interestingly, an emergent behavior usually occurs if a human agent (that cares) is involved if there are contradictions. A common situation is where a customer encounters a roadblock because the system doesn’t allow it, or is making it very difficult for the customer to get what they want, then a representative or an agent provides support to the customer through workarounds or ‘hacks.’

In some cases, we might discover that these behaviors of hacking are repeated similarly in different instances by different reps independently of each other. This pattern emerges because the service actors pick up certain behaviors to compensate for the inefficiency, or ‘lack,’ or purposefully onerous system. What the service actors do, in essence, is be mediators of two conflicting ecosystems. It seems justifiable to suspect that there is a deep type-0 conflict in the roles deliverers want to play in providing service and how they are trying to interact with the recipients, which are also contradicting the ecosystem they’re confined in—an ecotone between their projected ideals and the reality they have to work with.

Nevertheless, the result of this ecotone is an opportunity to make radical and systemic changes—an innovative reimagination of what the structure could be to address the type-0 conflicts between the service recipient and the service deliverer. There are various tools in service design that different organizations use differently. In our case, we can use the evolution map as a jumping-off point to illustrate how the ecotone framework could be useful. Generally, the evolution map consists of different horizons or phases to outline how various capabilities (new or modified) relate and evolve to reach the organization’s north star. If we identify specific pains related to type-0, there are two general approaches to the evolution map. Firstly, how can any emergent behaviors observed be capitalized to generate new concepts or used as a design inquiry (e.g., How Might We—) to generate more conversations and ideas? Secondly, if type-0 conflicts are identified, what kinds of structural changes (or new structures instilled) are needed to ensure the concept solutions can be carried out effectively and in alignment with the service recipients’ expectations? Often, this might be something like: how do we ensure there’s consistency in the behaviors of the service deliverers? How do we ensure the service deliverers provide service according to their expertise, passions, goals, etc.? The structural changes could be in the form of new regulations, changes in certain metrics or KPIs, or even changes in their mindsets and culture. Generally, we can ask, “What is broken: the interaction or the value exchange?”

The concept of ecotones is a useful framework for design practitioners and researchers (and whoever) to not only identify tensioned areas and understand the systemic cause of conflicts (type-0), but it also helps us understand and acknowledge that people are not defined just by their institutional functions, e.g., users, agents, market segments, and so on. To reiterate, the people we use as the subject of design and research are, first and foremost, human beings. They might act and behave in accordance with some general market conventions. But they are their individual selves, and at the same time, their individual beings are shaped by the worlds they inhabit. We should understand that when a service recipient steps into the domain of the service deliverers (and vice versa), they allow the other worlds to enter and overlap with their own domains.

Notes

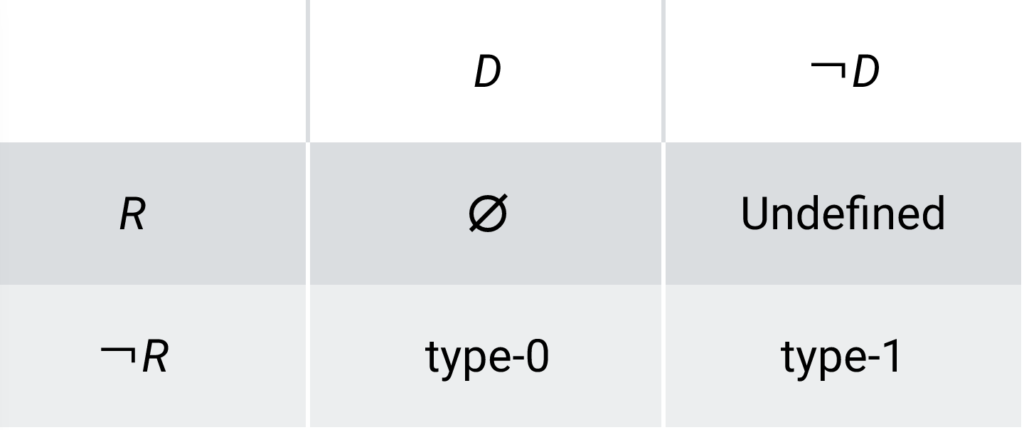

- There are other conditions that we do not outline in the main text above for brevity’s sake. Yet, it might be worth it to elaborate on them here. We can start with the basic elements. Suppose the end-users are service recipients, notate it as R to be defined as “service recipient’s expectation is correct.” The service deliverers, notate it as D to be defined as “service delivery is designed right or as intended.” (i) The first and obvious condition is when R is aligned with D, that is, the recipient receives the service as expected because the deliverer provides it as intended, which means that there is no contradiction (∅), thus: R ∧ D → ∅. (ii) When D and R are misaligned, that is the recipient’s expectation of the experience incorrect (¬R) because the delivery of the service is not design as intended (¬D), means that this is a contradiction in expectations, thus: (¬R) ∧ (¬D) → type-1. (iii) Another situation when D and R are misaligned where the recipient’s expectation of the experience is incorrect (¬R) but the delivery of the service is designed as intended D is a contradiction in principles, thus: (¬R) ∧ D → type-0. In summary:

i. R ∧ D → ∅ ; if receiving is correct and delivering is right, then there is no contradiction.

ii. (¬R) ∧ (¬D) → type-1; if receiving is incorrect and delivering is not right, then there’s a contradiction in meeting expectations.

iii. (¬R) ∧ D → type-0 ; if receiving is incorrect and delivering is right, then there’s a contradiction in principles.

The last condition (iv) is a bit confounding as it creates a logical impossibility—the recipient receives the service as expected R, even though the delivery of the service is not designed as intended (¬D), but that means the service is actually designed right or as intended (D), which defaults to the situation (i) R ∧ D → ∅. What becomes of the (iv) R ∧ (¬D) condition? We conclude that such a situation is impossible; thus, we can be satisfied just to call it undefined. We can summarize it in a table below:

- The choice of the word “tension” here is deliberate, specifically for service design, as the purpose of the framework is to expose hints of tensions existing between two ecosystems. Etymologically speaking, it is also most appropriate, as the ‘tone’ in ecotone (‘eco’ here is the short form of ecology) comes from the Greek τόνος (tónos), which literally means “tension”.

References

R. Leemans (ed.), Ecological Systems: Selected Entries from the Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-5755-8_9, # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

Pendleton-Jullian, A. (2020). In R. Barnett & N. Jackson (Eds.), Ecologies for learning and practice: Emerging ideas, sightings and possibilities (pp. 122–128). essay, Routledge.

Ryberg, T., Davidsen, J., Bernhard, J., & Larsen, M. C. (2021). Ecotones: A conceptual contribution to postdigital thinking. Postdigital Science and Education, 3(2), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00213-5

Originally published at thisisharmonic.com on March 21, 2023